Can Anti-Racism Spur Labor Organizing?

My survey findings on BLM's impact on the current unionization uptick

Can anti-racist activism feed into labor organizing and multiracial working-class organization? Or — as some leftists suggest — is anti-racism necessarily an elitist project of corporate America and “the professional managerial class,” which merely seeks to diversify business and professional summits?

A large-scale survey I conducted of worker organizers for my forthcoming book on worker-to-worker organizing can help shed light on this contentious debate. With the help of a research assistant, I reached out to every union drive that went public in 2022 — resulting in over 500 responses from worker leaders to my anonymous survey asking about their union drives and personal backgrounds.

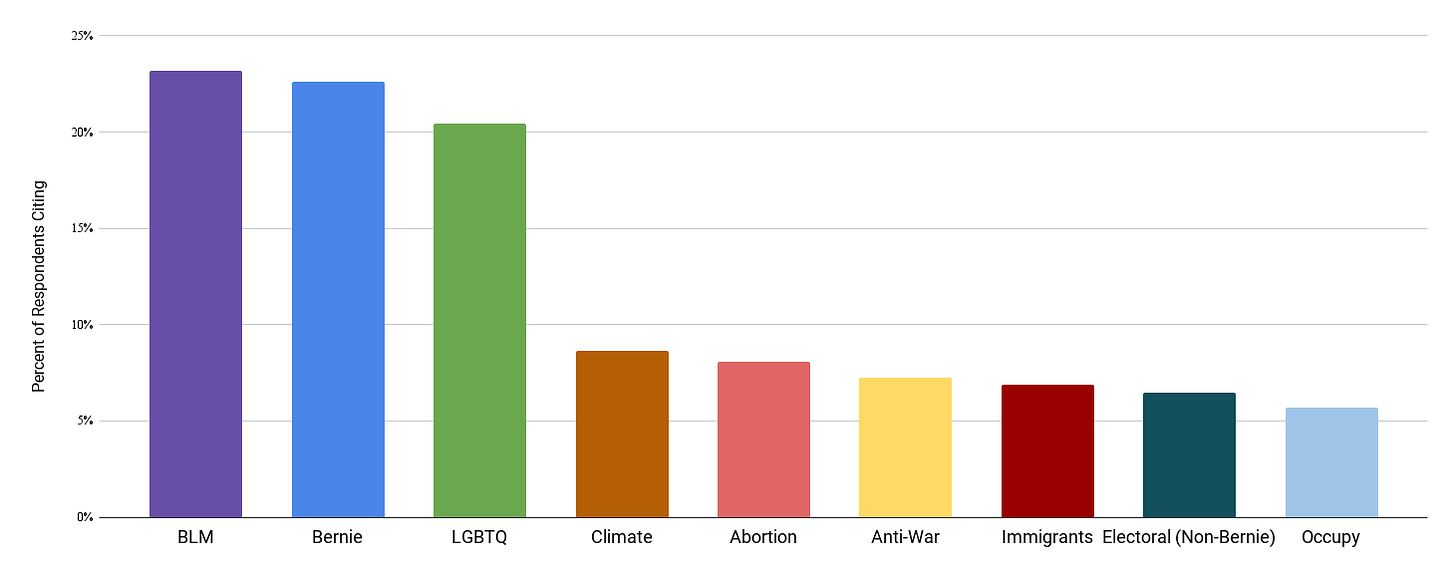

One of the more remarkable findings from this research was the extent to which Black Lives Matter protests fed into today’s labor uptick. My survey asked each respondent to list which, if any, external social movements had played a “major role” in inspiring them to unionize their workplace. What I found was that BLM was the (non-union) movement influence that was most widely cited by those workers who initiated union drives in 2022.

This graph summarizes my survey findings.

Non-union Movement Influences on Worker Leaders, 2022

Wells Fargo’s internal company memo was thus accurate enough in warning that “a new generation of employees with activist experience successfully unionized parts of major companies with no prior history of unionization.”

Corporate Anti-Racism

Critics are not wrong to identify the self-serving nature of much of what passes as anti-racism today. Business leaders, non-profit execs, and neoliberal Democrats have — under pressure from protests and public opinion — painted themselves in social justice colors, while studiously avoiding any meaningful distribution of resources or power downwards. Among these milieus, we’ve seen a flurry of milquetoast press releases, trainings on interpersonal etiquette, charity donations, and initiatives to diversify management positions.

Such commitments to social justice, however, do not extend to structural solutions like funding a robust welfare state rather than mass incarceration — or allowing employees to collectively bargain. To the contrary, accusations that unions are inherently racist have recently become a staple of union-busting propaganda. Firms like Littler Mendelson now fluently speak the language of anti-racism and tout the strategic importance of their attorneys’ diversity for keeping workplaces union free. In this same spirit, REI responded to its workers’ organizing efforts by putting out a union-busting podcast that began with an acknowledgement from Chief Diversity and Social Impact Officer Wilma Wallace that she was “speaking to you today from the traditional lands of the Ohlone people” and in which CEO Eric Artz framed his anti-union case as consonant with REI’s continued focus on “inclusion” and “racial equity.”

In contrast, recent labor struggles have tied fights against police brutality and systemic racism to pushes for multiracial working-class unity and economic redistribution. Indeed, demands for better pay were slightly higher among the drives of survey respondents of color compared to white respondents. My survey found that 90.4 percent of white worker leaders participated in drives where pay was a top demand; this was true for 91.3 of non-white respondents.

Leftists, in short, are justified in criticizing neoliberal anti-racism. But only focusing on this is one sided and strategically unhelpful. The recent labor uptick has clearly exposed the contradiction between corporate anti-racism and working-class anti-racism.

Working-Class Anti-Racism

Given that Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 were perhaps the largest in US history, it should not be that surprising that this insurgent energy fed into a wide range of workplace actions and organizing efforts.

Organizers at overwhelmingly non-white, low-wage workplaces like Staten Island’s JFK8 warehouse saw their struggle for better wages and working conditions as, among other things, a direct way to challenge racial injustice. Amazon further cemented this perception by relying on racist stereotypes to discredit Chris Smalls after they fired him. “I’ll tell you now, Amazon is definitely the new-day slavery,” responded Smalls on his short-lived YouTube show Issa Small World. “Just think of the job title [we do], it’s picker.”

Along these same lines, Burgerville workers — who had struck in 2018 for the right to wear Black Lives Matter and Abolish ICE buttons at work — posted the following to their Facebook page in late June 2020:

Earlier this week, Burgerville workers at the Montavilla Burgerville delivered a petition stating that BLACK LIVES MATTER IS A WORKPLACE ISSUE and demanding hazard pay, fair scheduling, and our right to wear antiracist buttons at work.…. We are not fooled by Burgerville corporate’s marketing campaign … we want real, meaningful change. Black Lives Matter in our fight for a living wage, safe conditions, and access to health care during a pandemic that disproportionately impacts Black people.

Across the US, skirmishes with management over meaningful support for BLM were an important starting point for numerous unionization efforts. Employees put up signs at work, wore BLM buttons and masks, and went with co-workers to marches. They also took this fight directly into their companies and institutions. “Throughout 2020, social justice issues showed themselves in the workplace more than in the past few decades,” lamented the notorious union-busters at Littler Mendelson.

Bosses were well aware of the contagion threat of any contestation at work, which is why companies like Whole Foods prevented employees from wearing BLM face masks. A leaked high-level internal company email explained that such actions might be “opening the door for union activity.”

Moe Mills, a St. Louis Starbucks partner, recalled to me that “what really woke me up to Starbucks’ progressive BS was that when George Floyd was murdered, partners came into work and got in trouble for wearing Black Lives Matter stuff. Starbucks sent out to everyone that political attire was against dress code and partners would be sent home. We were outraged — and it was only after Starbucks got canceled on Twitter because partners spoke up about this that they retracted the policy.”

At disproportionately white workplaces — e.g. in journalism and non-profits — collective demands for better pay were seen as a way to attract and retain more people of color. And the immediate organizational roots of more than a few union drives, such as Forge cafe in Somerville, Massachusetts began from ad-hoc co-worker digital chats and carpools set up to support BLM protests. Casey Moore, one of the workers in Buffalo who launched Starbucks Workers United, describes a similar dynamic nationwide: “When you’re going to huge protests and acting in solidarity in the streets, it’s not a big leap to ask ‘Why can’t we do that at our workplaces too?’”

Numerous worker leaders I spoke with saw workplace organizing as a particularly fruitful arena to fight for anti-racist change. Felix Allen, a worker at Lowe’s in New Orleans, explains his decision to unionize as follows: “There’d been so many huge protests against police murdering Black people, and I felt like unionizing my store, even if it wasn’t directly related to police brutality, was a way to make a real difference in people’s lives at a place where we could exert some degree of control.”

A similar dynamic shaped the political evolution of Leena Yumeen, a Columbia undergrad student and YDSA leader who helped initiate a successful drive to unionize Resident Advisors in the dorms:

Personally, I was politicized mostly through the Black Lives Matter movement and the experiences that I've dealt with as a woman of color. That’s what radicalized me — and it’s what radicalized a lot of young people. So I got into politics through issue based things and through further organizing I eventually realized that labor is at an epicenter of everything, that workplace organizing is a very useful axis from which to organize for all our issues.

This Juneteenth — as racial injustice continues to ravage communities from the United States to Gaza — it’s important to remember that there’s no road to working-class unity and power that doesn’t consistently combat all forms of oppression.

[This is a working paper. Feel free to share on social media, but please do not republish.]

Excellent.

"This is black, this is brown" Mindz of a Different Kind