Are Strikes Enough?

10 years after Chicago's strike, my reflections on the educators movement and working-class strategy

[In this article written for New Labor Forum, I take a look at the significance of the historic 2012 Chicago teachers strike, examine the K-12 movement since then, and raise some crucial questions about the limitations of strikes — and about what we still don’t know about how to build sustained working-class power and reverse neoliberalism. Would love to hear your thoughts!]

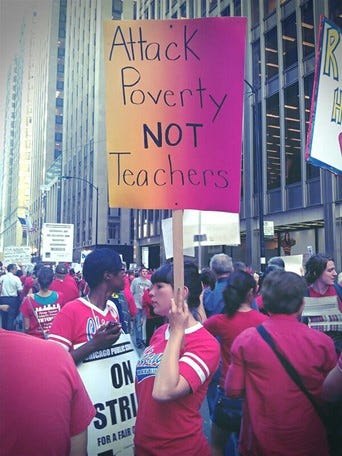

Ten years ago, Chicago educators lit the fuse of what eventually became a national teachers’ revolt. Faced with Democratic Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s privatizing agenda, over 26,000 teachers, clinicians, and paraprofessionals shut down schools for seven days in September 2012. The Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) won a 17 percent pay raise and increased resources for students, and it stopped a 40 percent increase in health care costs as well as a proposal to peg teachers’ pay to students’ standardized test scores. No less important, the union challenged the accepted truths of corporate education reform, built deep ties with community members, and empowered educators across the city and nation.

Pioneering an approach that has since come to be known as “bargaining for the common good,” Chicago educators demonstrated the power of worker-led unionism that fights with and for the broader multiracial working class. On the ten-year anniversary of the strike, it is useful to assess its historic significance and its impact on subsequent struggles nationwide, notably on the 2018 to 2019 wave of educator work stoppages that swept “red” as well as “blue” states. It is also important to identify some underexplored aspects of the CTU experience, such as the limitations of strikes, the dilemma of sustaining power, and electoral organizing in the wake of strike action. One way to prepare for the struggles ahead is to take a fresh look at what we know—and what we do not yet know—about how Chicago’s militant teachers made history.

The Significance of the 2012 Strike

Successful strikes often seem inevitable in hindsight. But we should not lose sight of just how novel and unexpected the CTU’s work stoppage was in 2012. Jean-Claude Brizard was the CEO of Chicago’s public school system at the time. As he put it—when he resigned in 2013—“We severely underestimated the ability of the Chicago Teachers Union to lead a massive grassroots campaign against our administration. It’s a lesson for all of us in the [education] reform community.”[1]

By 2012, mass job actions had all but disappeared in the United States—indeed, the year 2009 witnessed the fewest number of major strikes, five in total, since the Bureau of Labor Statistics began tracking labor conflicts.[2] In addition to bucking the trend, the Chicago teachers’ strike was not just any other work stoppage. It was an action that explicitly challenged the entire neoliberal education reform agenda of privatization and union busting, a struggle that pitted the CTU and its community allies against a powerful Democratic Party establishment.

From 1999 to 2009, the number of students enrolled in U.S. charter schools quadrupled, and during the Great Recession an ongoing bipartisan offensive against the public sector and its unions was ratcheted into high gear.[3] The Obama administration’s signature “Race to the Top” national grant policy—based in part on Chicago’s earlier “Renaissance 2010” program, which punished schools with low test scores—pushed competition, overhauls or closures of “failing” schools, standardized testing, and merit pay. Teachers were demoralized, and the National Education Association (NEA) and American Federation of Teachers (AFT) leaders often seemed more interested in accommodating themselves to corporate education reform policies than in fighting them. To quote author and education reporter Dana Goldstein, AFT president Randi Weingarten was “trying to carve out a conciliatory role for herself in the national debate over education policy.”[4]

Demonstrating the potential for rank-and-filers to successfully transform a moribund union, the left-led Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators (CORE) won the CTU’s leadership in 2010, with a mandate to empower members to take on privatization, austerity, high-stakes testing, and the systematic underfunding of schools serving students of color. As one CTU organizer later recalled, in school-site meetings preparing for the coming contract in 2012 organizers would start off the discussion as follows: “If any of you think the next contract is about a percentage-point raise, tell us, because we think we know it’s about the future of public education as we know it: that’s what’s on the table.”[5] This was not just rhetoric. Chicago’s Democratic Party machine under Mayor Rahm Emanuel—Barack Obama’s former chief of staff—was promoting a sharp uptick in closures of neighborhood public schools in Black and Brown communities, for the benefit of privately run, publicly funded charters.

Chicago’s 2012 strike was the first serious union challenge to the bipartisan reform consensus on K-12 schools. And it was a significant move away from organized labor’s longstanding deference to Democratic leaders. “While most American unions have been terrified to break with any sections of the Democratic Party, even those pushing neoliberal policies that are throwing those unions’ very existence into question, the CTU has not,” writes Jacobin editor Micah Uetricht in the book, Strike for America: Chicago Teachers Against Austerity.[6]

Under the inspired leadership of then CTU president Karen Lewis, the union put forward a compelling alternative for public education in Chicago and across the United States. As made clear in its highly publicized 2012 white paper, “The Schools Chicago’s Students Deserve,” Chicago educators were fighting for “common good” issues that went well beyond pay raises. With demands such as smaller class sizes and hiring more nurses as well as social workers, Lewis explained on the eve of the strike that drastic action was necessary to “show we are serious about getting a fair contract which will give our students the resources they deserve.”[7] Data in hand, CTU leaders rejected the logic of austerity, explaining that resources did exist to provide a great education to all students. Achieving this goal, the union declared, would require a major redistribution of wealth through taxing the rich and financial transactions as well as ending the millions of dollars in subsidies doled out to large real estate developers through the city’s Tax-Increment Financing program.

In this process, the CTU—unlike so many K-12 unions before it—successfully wrested the banner of racial justice away from neoliberal education reformers, who argued that the longstanding racial inequities in K-12 schools could only be resolved through strengthening charter schools and weakening unions. Denouncing “educational apartheid” in Chicago, the CTU charged district leaders with deepening racial inequalities, particularly through school closures. Austerity and privatization, the union insisted, disproportionately hurt communities of color. And as a Black educator leader, Lewis was not afraid to call out perceived hypocrisy:

Rich white people think they know what’s in the best interests of children of African-Americans and Latinos . . . There’s something about these folks who use little black and brown children as stage props at one press conference while announcing they want to fire, lay off, or lock up their parents at another.[8]

By combining social justice demands with rank-and-file engagement and a willingness to take disruptive action, CTU set itself apart from most other unions and inspired teachers across the country to follow its example.

The Movement Goes National

CTU efforts in 2012 did not immediately initiate a wave of work stoppages—in contrast with the West Virginia strike of 2018—nor did they draw national attention to labor struggles to the same degree of unionization efforts today at Starbucks and Amazon. But in various ways, the roots of these recent upsurges can be traced back to Chicago.

West Virginia’s explosive 2018 statewide walkout was initiated by radical rank-and-file teachers who collectively studied, and sought to replicate, the lessons of Chicago.[9] Faced with ineffective educators’ unions and looming health care increases in West Virginia, Charleston teacher Jay O’Neal began reading everything he could about CTU and the 2012 strike, including Micah Uetricht’s Strike for America and a book published by Labor Notes, How to Jump-Start Your Union.

In the summer of 2017, O’Neal organized a democratic socialist educators’ study group around the book, No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age by Jane McAlevey, a manual and manifesto for working-class strategy in which the story of CTU and the 2012 strike plays a major role. For Emily Comer, who in the fall of 2017 cofounded with O’Neal the viral Facebook group West Virginia Public Employees United, the main political upshot of the McAlevey book was its “clear analysis of the difference between real organizing and advocacy.” Whereas CTU had empowered member leaders to organize their coworkers and communities, West Virginia’s unions were focusing on lobbying politicians. In this respect, Comer says, the West Virginia unions weren’t “building real power.”[10]

After months of build-up—through rallies, community outreach, one-day wildcat walkouts in southern counties, and an outpouring of Facebook-fueled deliberations—West Virginia’s unions were eventually pushed by the rank and file to back a statewide strike, which lasted from February 22 through March 6, 2018. Garnering national headlines and galvanizing parents, students, and other public employees, West Virginia educators succeeded in defeating a proposal to dramatically increase healthcare costs for public-sector workers and they won an across-the-board five percent raise for all state employees.

Chicago’s impact on the national teachers’ revolt was even more direct in Arizona. One of the core leaders of Arizona Educators United (AEU)—the new rank-and-file group that in March 2018 initiated the state’s movement for increased pay and school funding—was Rebecca Garelli, a Chicago native and teacher who had participated in the 2012 Chicago strike. Garelli explains that her politicization took place primarily through the CTU:

That union militancy, for me, it all comes from Chicago. It was real democratic unionism. People who weren’t political, it made them political—and it sparked such camaraderie and solidarity in our building. Then when we were actually on strike [in 2012], marching in downtown Chicago, it was epic. We were under the high-rises and we’d see workers everywhere supporting us, waving, holding signs . . . It created this sense of unity and it politicized a lot of people in the process.

Garelli leaned on her CTU experience to help AEU build up a site-liaison network of 2,000 rank-and-file teacher leaders across the state of Arizona in the spring of 2018, envisioning and coordinating an ambitious plan of escalating actions to involve educators and win over wavering parents: “I knew from Chicago that we had a lot of work to do before we were ready for something like a strike, particularly a statewide action.” The work paid off. In late April, tens of thousands of Arizonan educators walked out to demand better pay and more funding for their students. By shutting down schools across the state, they forced Governor Doug Ducey, a billionaire-funded Republican, and the state legislature to cave to some of their central demands. The [Arizona] strike won over $300 million in additional funding for schools and a 20 percent educator raise over the next four years, while preventing these gains from being funded by cuts to other social services.

Chicago’s influence was not limited to so-called red states. In the wake of 2012, rank-and-file teacher formations seeking to replicate the approach of the CORE caucus blossomed across the country, coming together in particular through the national United Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators (UCORE) network. Arlene Inouye—a teacher and UCORE activist in Los Angeles—was one of thousands of educators for whom CTU showed that a different type of unionism was possible:

Chicago was the spark of the movement that has swept this country in recent years. We were so inspired and uplifted by CTU—they were really the first major teachers’ unions to bring back the strike, to expose the privatizers, to develop authentic parent-community coalitions to win the schools our students deserve, and to call out the racism of school closings in communities of color.

Inspired by Chicago, Inouye and like-minded organizers such as Alex Caputo-Pearl and Cecily Myart-Cruz founded Union Power, a Los Angeles teachers’ caucus. After unseating the old leadership of the United Teachers Los Angeles (UTLA) in 2014, Union Power began to revitalize their union through systematic deep organizing in the schools and the broader working class. A four-year organizing drive culminated in January 2019, when UTLA’s momentous strike paralyzed the country’s second-largest school district and won lower class sizes, a six percent pay raise, an end to racist “random searches” of students, a full-time nurse in every school, as well as additional counselors and librarians.[11]

The 2018 to 2019 national teacher upsurge gave a significant momentum boost back to the CTU, which had suffered a series of setbacks after 2012, not least of which was Mayor Emanuel’s successful 2013 drive to close 50 neighborhood schools. CTU activist and teacher Debby Pope explains that as the insurgent educators’ “movement has spread, it in turn has given back to us in Chicago and sustained us as a short-term struggle morphed into a national movement for educational justice.” Testifying to this reciprocal dynamic, Chicago educators struck again in 2019—this time together with support staff and park workers of Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Local 73. And whereas much of the 2012 strike was focused on warding off the worst of Rahm Emanuel’s attacks, CTU’s most recent work stoppage was an almost entirely offensive struggle to reverse the damage done by years of austerity and corporate education reform. Educators this time around won millions of dollars to lower class sizes and hire hundreds of new social workers, nurses, and librarians, in addition to receiving a 16 percent pay raise over the coming five years.

The two Chicago strikes, like the broader 2018 to 2019 educator upsurge, wrested important concessions for educators and students. But perhaps their greatest cumulative impact was in shifting public opinion on education policy and organized labor. Blame for the crisis in K-12 schools began to get directed at systematic underfunding and low pay, rather than at alleged inefficiencies of trade unions and the public sector. Testifying to this sea change, not only did AFT and NEA leaders start to more consistently challenge neoliberal education policies, but even establishment Democrats such as Joe Biden dropped their former advocacy of privatization and pledged to support many of the educator movement’s demands in their 2020 presidential campaigns, from tripling Title I funding, to boosting teacher pay, to hiring more mental health professionals. No less important, educator strikes organized or inspired by the CTU have played a significant role in making the public more favorable to organized labor.[12]

To be sure, systematic problems in K-12 are very far from being resolved and the 2018 to 2019 educator offensive was thrown backwards almost overnight by the onset of Covid-19 in early 2020. Polarizing debates over school closures and “critical race theory” proceeded to engulf countless districts, particularly in Republican-dominated states. To make things worse, pandemic conditions have exacerbated public education’s longstanding problems and stressors. With schools now scrambling to deal with remote learning, student traumas, and ongoing Covid safety concerns, issues of understaffing, underfunding, and excessive workloads became especially trying. Unsurprisingly, a quarter of teachers—and almost half of Black teachers—by late 2021 indicated in national surveys that they were considering leaving their jobs. For many, the work of teaching had become too stress-inducing to be sustainable.[13] Yet unlike ten years ago, CTU is now no longer almost entirely alone in its fight for the schools that students deserve. With districts returning to in-person instruction, K-12 strikes have also returned; Minneapolis and Sacramento educators walked out earlier this year for better pay and increased student resources. And now that new unionization drives are blossoming in the private sector, and inspiring worker organizing across the country, it is likely only a matter of time before educators pick up where they left off in 2018 to 2019.

Underexplored Issues: The Limitations of Strikes

As a paradigmatic social justice movement in the United States, the CTU has received a considerable amount of academic and activist attention since 2012. But some key facets of the union’s experience—and of militant labor organizing more generally—remain under-explored.

After decades of declining strike rates and union risk-aversion, activists and scholars inspired by CTU have emphasized the power of workplace disruption as a means of wresting concessions from employers, transforming workers, and revitalizing unions. This is an important strategic corrective. Nevertheless, it is also necessary to start rigorously analyzing the limitations of work stoppages. None of the education strikes from Chicago 2012 up through Minneapolis 2022 have entirely met the expectations of their participants—indeed, Emanuel’s closures of fifty schools in 2013 was in part made possible by the inability of the CTU strike to win strong financial payouts to teachers whose schools were closed. Leftist scholars, journalists, and organizers tend to gloss over the tension between the dramatically increased expectations generated by militant work stoppages and the resulting contractual outcomes.

Though educator actions—from West Virginia to Los Angeles to Chicago—did bring about major gains, and achieved more than years of backroom lobbying have achieved, they did not decisively reverse decades of neoliberal policies. As an on-the-ground observer of the most recent teachers’ work stoppages, I have witnessed a substantial minority of workers in even the best of strikes express their strong disappointment in the contracts that resulted. Underfunding, low pay, high class sizes, and excessive standardized testing remain endemic.

Disruptive actions are essential for building working-class power, but the available evidence suggests that they are not enough on their own. There is only so much that a single work stoppage can normally achieve, particularly when it is limited to one school district and when corporate politicians on state and federal levels continue to underfund public services. To win a transformational reinvestment in K-12 schools, CTU, UTLA, and other left led unions are also deeply invested in the electoral arena. In 2014, for instance, Karen Lewis seriously considered a run for mayor and was even leading in early polls. Though health problems forced Lewis to stand down, the CTU remained deeply involved in city political fights, playing a major role in Rahm Emanuel’s eventual downfall as well as the 2019 election of six democratic socialists as city aldermen. Yet there remains a surprising paucity of rigorous research on Chicago teachers in politics, reflecting a broader lack of scholarship on contemporary unions’ electoral efforts. Until we know exactly what is being done electorally as well as what is (and is not) working, it will be hard for union leaders and allied scholars to help maximize the effectiveness of “bargaining for the common good” strategies.

Finally, scholarship on social justice unionism tends to focus on peak periods of mobilization rather than what comes in their wake. What are the best practices in left union governance? How do unions such as the CTU seek to effectively maintain member engagement when a strike is not looming? What lessons can be learned from Chicago about how militant union leaders relate to the rank-and-file caucuses that helped elect them into positions of power? Answering questions of this sort will not only fill a lacuna in the literature, it will also inform the governance practices of a new generation of militant union leaders, as an increasing number of opposition caucuses win the helm of a much weakened and hollowed-out labor movement.

Bottom-up internal union transformation remains most prevalent in K-12 teachers unions. But, as the Teamsters’ recent election of a new progressive national leadership suggests, it is spreading to the private sector as well. It behooves labor academics and activists to pay more attention to the processes and dilemmas of sustaining bottom-up power through the governance of militant workers’ institutions.

Revitalizing labor may begin with risky actions like work stoppages or insurgent unionization drives, but it cannot end there. Though strike action is a more exciting topic than electoral politics and organization building, further investigations may reveal the myriad of ways these two factors determine the long-term impact of victories won through workplace militancy. A decade after Chicago’s historic strike, labor research should start reflecting the fact that the CTU was, and continues to be, a pioneer in more ways than one.

Notes

1. Alex Parker, “Jean-Claude Brizard: We ‘Underestimated’ Teachers Union,” August 22, 2013, available at https://www.dnainfo.com/chicago/20130822/downtown/jean

2. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Annual Work Stoppages Involving 1,000 or More Workers, 1947—Present,” available at https://www.bls.gov/web/wkstp/annual-listing.htm.

3. National Center for Education Statistics, “Charter School Enrollment,” available at nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=30.

4. Dana Goldstein, “The Education Wars,” March 20, 2009, available at https://prospect.org/features/education-wars/.

5. Cited in Jane McAlevey, No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 122.

6. Micah Uetricht, Strike for America: Chicago Teachers against Austerity (London: Verso Books, 2014), 98.

7. Faith Karimi, “Chicago Braces for Possible Teachers’ Strike — Its First in 25 Years,” September 7, 2012, available at https://www.cnn.com/2012/09/07/us/chicago-braces-for-possible-teachers-strike-its-first-in-25-years/index.html.

8. Ted Cox, “CTU’s Karen Lewis Blames ‘Rich White People’ for Education Inequity,” June 18, 2013, available at https://www.dnainfo.

com/chicago/20130618/river-north/ctus-karen-lewis-blames-rich-white-people-for-education-inequity/.

9. For a full discussion of the 2018 strikes, see Eric Blanc, Red State Revolt: The Teachers’ Strike Wave and Working-Class Politics (London: Verso Books, 2019).

10. Unless otherwise noted, all educator quotations in this article are from semi-structured interviews conducted by the author between March 2018 and May 2019.

11. On the Los Angeles strike, see Jane McAlevey, A Collective Bargain: Unions, Organizing, and the Fight for Democracy (New York: Ecco, 2020).

12. Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, Suresh Naidu, and Adam Reich, “Do Teacher Strikes Make Parents Pro- or Anti-Labor? The Effects of Labor Unrest on Mass Attitudes,” 2019, available at https://equitablegrowth.org/working-papers/do-teacher-strikes-make-parents-pro-or-antilabor-the-effects-of-labor-unrest-on-mass-attitudes/.

13. Elizabeth D. Steiner and Ashley Woo, “Job-Related Stress Threatens the Teacher Supply: Key Findings from the 2021 State of the U.S. Teacher Survey,” available at https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1108-1.html.